| «back to publications |

GREECEThe Whole Story by |

|

FOR "YVONNE" Cairo - Athens - London |

|

| CONTENTS | |

| CHAPTER | |

| I | THE BACKGROUND |

| II | THE KING - THE DICTATORSHIP |

| III | THE ALBANIAN WAR |

| IV | THE GERMAN INVASION |

| V | THE OCCUPATION |

| VI | CAIRO AND WHITEHALL |

| VII | RESISTANCE |

| VIII | THE GUERILLAS |

| IX | THE 'NATIONALISTS' |

| X | BRITISH POLICY |

| XI | 'NATIONAL UNITY' AND LIBERATION |

| XII | THE FINAL CRISIS |

| XIII | THE CIVIL WAR |

| XIV | THE REACTION |

| XV | CHANGES IN WHITEHALL |

| XVI | U.N.O. DECIDES |

| CONCLUSION | |

| THE FINAL VERDICT | |

| DIARY OF EVENTS | |

| LIST OF MAPS |

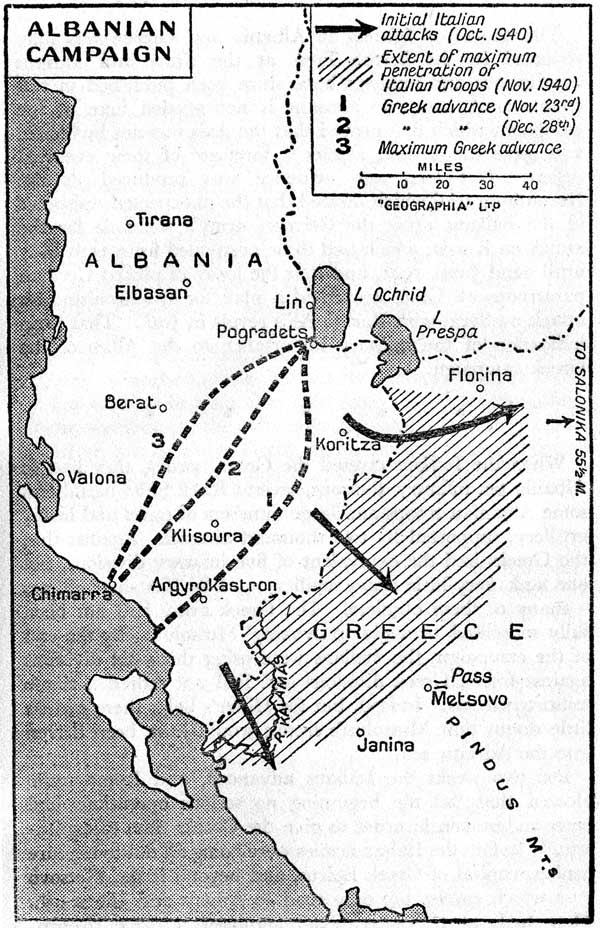

| ALBANIAN CAMPAIGN |

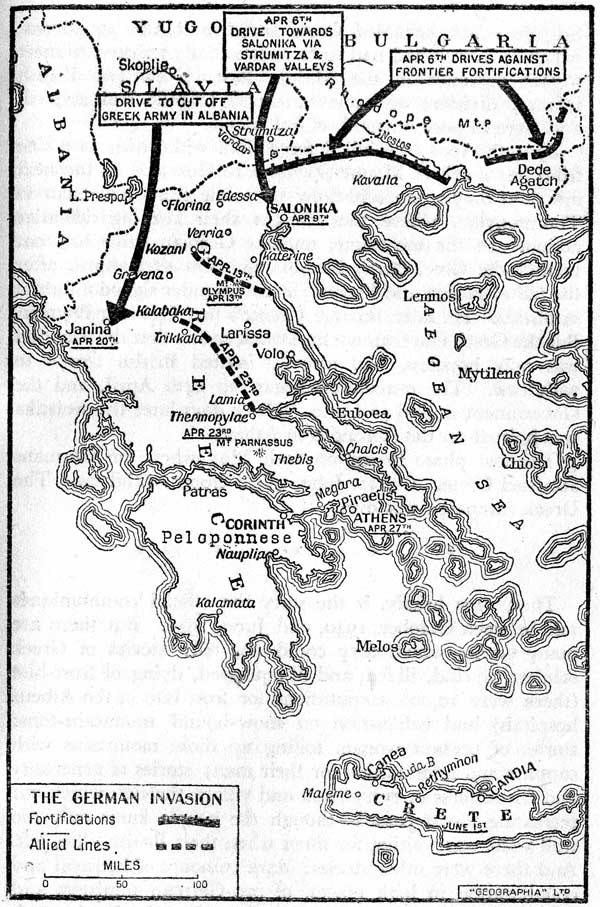

| THE GERMAN INVASION |

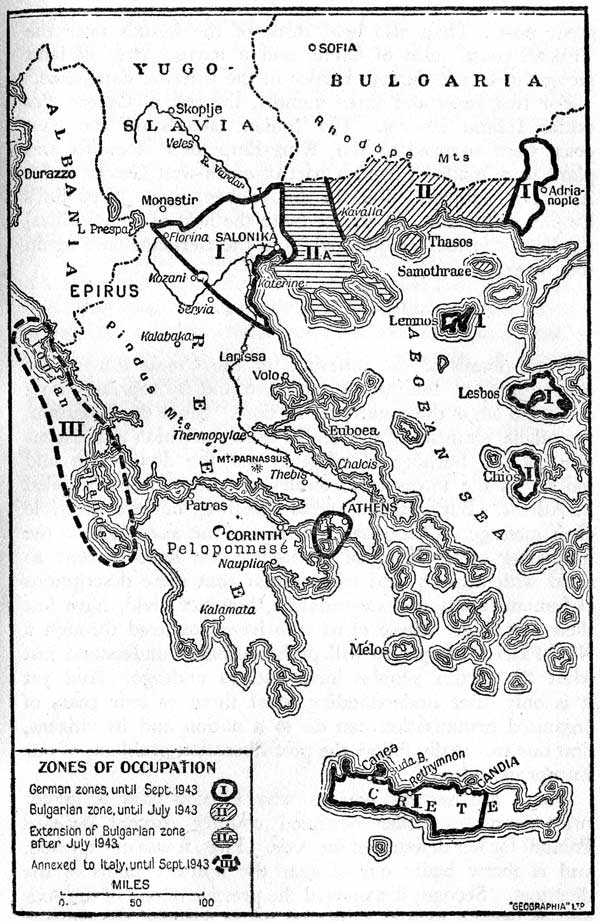

| ZONES OF OCCUPATION |

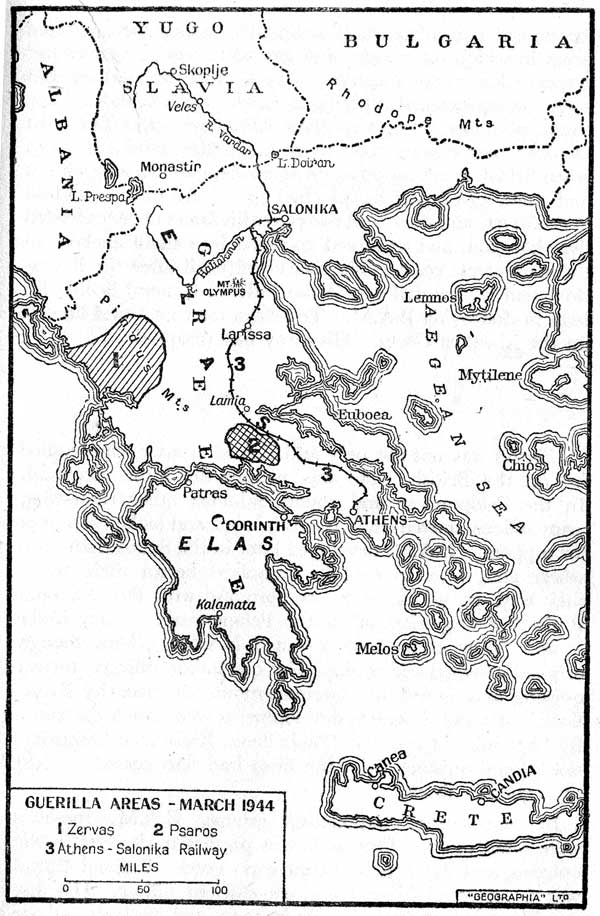

| GUERRILLA AREAS - MARCH 1944 |

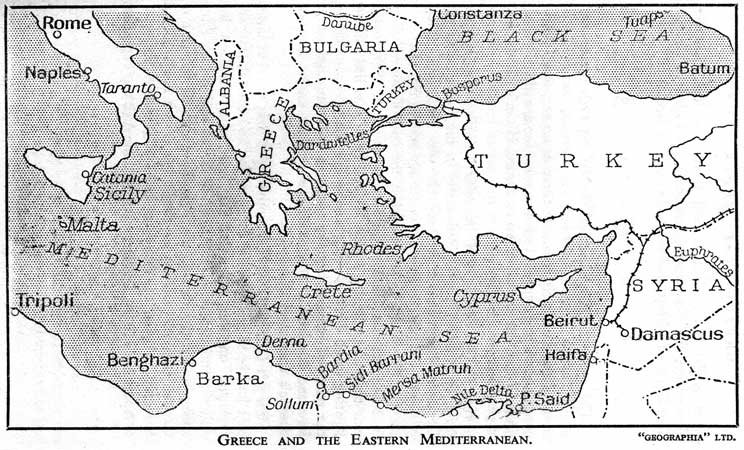

| GREECE AND THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN |

CHAPTER I»top

The Background

GREECE, more than any other ally in World War II, has aroused the admiration, sympathy and concern of the British people. Admiration for the stand she took when Britain was alone and facing defeat after Dunkirk; for her victories over the Fascist armies in Albania in 1940; and for her fight against overwhelming Nazi forces in the spring of 1941. Sympathy for the hideous sufferings of her people during the occupation, and for the brave resistance with which they met them. Concern lest her political troubles, which led to the mad nightmare of Greeks and British soldiers killing each other a few weeks after the liberation, should now rob her of the rewards of hard-won victory.

This country, and every one of the United Nations, are still under a great and binding obligation to the Greeks. Only history can tell just how much we owe them for the defeat of Hitler; but we already know that but for the Greek campaign of 1940-41—those vital six months which delayed the attack on Russia and stopped the junction of Axis forces in the Middle East—we might not yet have been at peace. Until Greece is once again a prosperous, independent and democratic country, our obligation will not have been discharged.

Yet to-day, Greece is far from prosperous, is independent only in name, and is without many of the essential features of real democracy. She became the subject of international discussion and international disagreement. What, then, went wrong? What happened in Greece?

* * * * *

Before the war, few Britons knew much of Greek affairs. The archaeologist busied himself with classical research, the occasional tourist hurriedly `did' the sites and came home struck only by the beauty of the country and the charm of its peasant population. In 1936 Fascism came to Greece, and the security police saw to it that very little political information reached the outside world. Then, with the war, and more particularly after the occupation, a blanket of secrecy descended on Greek affairs. For four years, despite the curiosity of War Correspondents in the Middle East, no one in this country except the Cabinet, the Foreign Office, and our Intelligence Services, knew what was really happening `inside.' And so the British public were puzzled when at last the first Press reports did arrive—telling of fighting in the streets of Athens, of `red atrocities,' and `monarcho-fascist counter-terror.' It is not surprising that they should still be puzzled now.

But the need for secrecy has gone. The story of occupation and resistance and civil war, of military revolts and British intervention can now be told. It must be told if the people of this country are to understand what is happening to-day, if the United Nations are to make a fair judgment of British policy in Greece.

* * * * *

Modern Greek politics are not difficult to understand. There is a popular fallacy that there is something peculiar and complicated about the political behaviour of Greeks. That may be partly because reading• the British Press one is apt to get confused by a mass of names of places and politicians and generals which one cannot pronounce, or to compare our own relatively stable system with what seems to consist mostly of sudden changes, revolutions and military coups d’état. Those are the details and the symptoms—what is important is what lies behind.

* * * * *

The Greek Empire of Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Within 20 years practically all present-day Greece was under Turkish occupation which lasted for four centuries and left the country devastated and backward with a population of three-quarters of a million. In 1829, after a nine-year war of independence, the European Powers recognized a part of mainland Greece and a few of the Greek islands as a sovereign state, and, a little later, appointed a German prince as absolute monarch over the Greeks. Since then, the basic factors in Greek politics have been:

(1) The gradual liberation of Greek populations living outside Greek frontiers. This process was practically complete after the fall of Smyrna in 1922, when one and a half million Greeks from Asia Minor were exchanged for the Turks still left in Greece, and another exchange of populations was arranged between Greece and Bulgaria. Since then, foreign minorities inside Greek frontiers have been unimportant, and, with four exceptions (the Dodecanese islands, Cyprus, Eastern Thrace, and part of South Albania), there are now no Greek minorities abroad. Greece had become a unified national state by 1922.

(2) The struggle for a constitutional government, which began soon after the German King Otto's arrival (he finally abdicated in 1862), was continued under the Danish Glϋcksburg dynasty (to which the present King George II belongs), and has not yet been settled.

(3) The movement for social progress and `economic liberation' by the peasants and, later, the working people of the towns—a movement common to all Balkan countries between the two world wars. Advances were made under Liberal governments in the 1920's and early 30's, but reaction set in and culminated in the 1936 Fascist dictatorship. Occupation and resistance gave a great impetus to popular forces throughout Greece (and indeed, throughout Europe), and for them liberation' came to mean, to a greater or lesser degree, not only military victory but also winning the Atlantic Charter's 'four freedoms.'

These three factors (after 1922, the last two) are what lay behind the constantly shifting Greek political scene since Greece became an independent state a hundred and seventeen years ago. But independent though she technically was, Greece has often been the plaything of European power-politics. In the last century, her `protecting powers'—Britain, France and Russia—were principally interested in her and her expansion as a threat to the decaying Turkish Empire. Consequently their attitude towards her was largely determined, year by year, by their desire or otherwise to weaken Turkey. In World War I, Greece was, for a time, divided into two nations: one-half ruled from Athens by a 'neutral' but pro-German king, the other half from Salonika by a pro-allied Prime Minister. Her disastrous defeat by Kemal in 1922 was partly the result of British encouragement to land troops in Smyrna, followed by French and Italian assistance to the Turkish nationalists. For a time, after that, she was more or less in control of her own destinies, but dependent on international help in resettling her refugees, and to some extent under foreign financial control. Then, with the rise of Fascism in Europe, Greece, like the rest of the Balkans, was forced to get into line. A German `economic colony' by 1936, in that year she too went Fascist.

CHAPTER II»top

The King—The Dictatorship

King George II of Greece is now in exile for the third time. When his father King Constantine was forced to abdicate by the Allies in 1917 because of his pro-German sympathies (his wife was Kaiser Wilhelm's sister), Prince George, as he then was, was expelled with him, partly because of his Prussian military upbringing, and his younger brother, Alexander, was put on the throne. Three years later Constantine was recalled to Greece, but again abdicated in 1922 after the Smyrna defeat: King George succeeded him. His first reign lasted one year. Then, his suspected connection with an attempted military rising led to a second exile, mostly spent in London. In 1935, with a 97 per cent majority in a plebiscite `managed' by a Right-wing military dictator, he returned. He sacked the dictator, and for one year Greece enjoyed her last period of constitutional parliamentary government. Then a new dictatorship came to power: the Fascist regime of General Metaxas. When King George left to escape the Axis invaders in April 1941, many Greek democrats associated him with Greek Fascism, and the bitter hatred it inspired among them followed him into his third period of exile.

* * * * *

Briefly, the history of the Metaxas dictatorship is this: Alter the elections of 1936, the last free elections to be held in Greece, 15 Communist members held the balance between the big Liberal and Conservative blocks in Parliament. King George first appointed a non-party government under an ex-university professor. The latter died within a few months, and was replaced by General John Metaxas, leader of a very small Right-wing parliamentary grout). The General at once claimed that his `program me of reforms' would be hampered by ordinary parliamentary procedure. Parliament agreed to its own suspension for five months, and Metaxas was empowered to govern by decree, but a parliamentary committee was set up in which each party was proportionately represented.

Metaxas' appointment of Right-wing friends and supporters to key positions, however, soon provoked strong opposition and protests, and when the Trades Unions threatened to call a general strike on the fourth of August, he forestalled them by a coup d’état. Parliament was formally abolished (its building was taken over as headquarters for the `National Youth'), all other political leaders who had protested to King George against the dictatorship were either exiled or put under house-arrest, and the `Third Civilisation' with all the usual Fascist features—Labour Battalions, censorship, security police, concentration camps, a Ministry of Propaganda, etc., etc.—was set up.

During the dictatorship the old democratic parties virtually ceased to exist. The efficiency and ruthlessness of Metaxas' Minister of Public Security made any active or vocal protest almost impossible. The Communist Party alone, despite the attentions of government spies and agents, worked underground and managed to preserve some of its organisation. But it was not until after the German occupation that the full extent of the Greeks' hatred of Metaxas became apparent. How it did so is described later.

* * * * *

The reaction against Metaxas was twofold. The Greek people, great individualists, detested any restriction of their political liberties. Almost more, they detested what they felt was a system copied from Hitler and Mussolini. And they could not forget that Metaxas, a staunch supporter of King Constantine, had been against helping the allies in World War I. Even after World War II began, many of them believed that he was still pro-German at heart. They were proved wrong: but a number of his leading supporters did in fact turn Quisling during and after the invasion. The King was involved because, having appointed Metaxas and sanctioned his methods, he was regarded as co-author of the dictatorship. In this way the old Royalist-Republican feud, which had started more than a hundred years before in King Otto's reign, broke out again in a new form. By the beginning of the occupation, most Greeks would have described the constitutional issue as Dictatorship, represented by Metaxas (who had died in January 1941) and the King (by then in Egypt), versus Democracy, represented by the resistance movements (then just starting) inside Greece. The cleavage became more complicated later. But, first, the story of the Albanian campaign must be told.

CHAPTER III»top

The Albanian War

In the small hours of the morning of 28th October 1940, the Italian Minister in Athens called at the house of General Metaxas. He was received by the Greek Premier in his dressing-gown. By then the world knew that the invasion of Greece was imminent. `Incidents' had already been staged by the Italians on the Greek-Albanian border, for weeks the Fascist Press and radio had been playing-up imaginary British violations of Greek neutrality, and Metaxas had already appealed, unsuccessfully, to Hitler to restrain his fellow-dictator. The Minister presented a three-hour ultimatum. He demanded "as a guarantee alike of the neutrality of Greece and the security of Italy, the right to occupy … a number of strategic points in Greek territory." He could not say which `strategic points' his government had in mind.

Metaxas replied that Greece would fight. Within two and a half hours—even before the ultimatum expired, and long before the Italian commanders in Albania could have known the answer—Italian troops were advancing into north-west Greece. Shortly afterwards Mussolini explained, "After showing exemplary patience over a long period, we have torn the mask from a people guaranteed by Great Britain—a servile people, the Greeks. It is an account that had to be settled." Clearly, he expected to settle it without much trouble. Britain was then alone and facing the imminent threat of German invasion. The rest of Europe was either already occupied or busy making pacts with Hitler. It was obvious that Greece could not expect much help from other countries.

* * * * *

»top

The course of fighting in Albania and Greece was fully reported in the British Press at the time, and various descriptions and analyses have since been published in this country. A complete account is not needed here of the campaign which first proved that the Axis was not invincible and gave the Italian armies a foretaste of their eventual defeat. Not long ago evidence was produced at the Nuremburg trial which showed that the unexpected resistance in the Balkans upset the German army's schedule for the attack on Russia, which had to be postponed from 15th May until 22nd June, 1941, and that the losses of picked German paratroops on Crete prevented a plan for synchronising an attack on Syria with Rashid Ali's revolt in Irak. That is an indication of the military importance to the Allies of the Greek campaign.

* * * * *

When the Italians crossed the Greek border, they had in Albania ten infantry divisions, several Black Shirt battalions, some Albanian troops and large numbers of tanks and heavy artillery, supported by two thousand aircraft. Against this, the Greeks had the equivalent of five infantry divisions, not one tank, very little heavy artillery and 84 `first-line' planes —many of them obsolete. The Greek army had not been fully mobilised to avoid `provoking' Mussolini. By the end of the campaign, the Italians were using thirty-six divisions against fifteen Greek divisions and had not scored a single military success. Indeed, but for Hitler's help, there can be little doubt that Mussolini's troops would have been driven into the Adriatic sea.

For two weeks the Italians advanced, and Rome radio gloated that "at the beginning no serious operations had been undertaken in order to give the Greeks time to capitulate." In fact the Italian armies were going all out to capture Janina, capital of Greek Epirus, and beyond it the Metsovo Pass which carries the only road to Athens and the south. They had, at the same time, launched a drive towards Florina, in the hope of reaching the Aegean and taking Salonica. Both attempts failed and by 14th November the Italians were everywhere on the defensive. The first and most notable Greek victory was the battle of the Pindus gorges when the 3rd Alpini Division-14,000 fully equipped Italian mountaineers—were met and routed by 8,000 Greeks, who not only compelled them to withdraw but almost closed their only exit. From then on, the only Italian soldiers on Greek soil were prisoners of war, and success followed success. Koritza, third biggest town and chief Italian base in Albania fell on 22nd November. On the 23rd the Greeks had captured Pogradets. Arghyrocastro, base of the Italian 11th Army, fell on 8th December, and by 28th December Greek forces had reached a line, from Pogradets to Chimarra, between 80 and 100 miles behind the farthest point reached by the Italians in their first offensive. Then the appalling winter weather in the Albanian mountains and the effect it had on the primitive Greek supply columns (mostly trains of pack mules) brought operations to a standstill.

* * * * *

But on 10th January the second phase of the Albanian campaign began. All chances of a serious Italian counter-offensive threatening Greek territory were over by then, and the Greeks were aiming at the capture of Valona, Berat and Elbasan as the first stage towards Durazzo and the capital, Tirana. That day they took Klisoura, key to Central Albania, and General Soddu, Italian C.-in-C., who had predicted it would be the 'tomb of the Greek Army' was sacked. Cavallero, the new commander, started a series of counter-attacks (forty-six were reported in one month) with much larger mechanised forces and without regard to casualties. They failed, and on 9th March a final great offensive, under the personal supervision of Mussolini, was launched. Eighteen days later Mussolini went home: the Greek lines were still intact. After five months of disaster his `account' with the Greeks had not been settled.

CHAPTER IV»top

The German Invasion

Meanwhile, Hitler had been preparing to come to Mussolini's rescue: German military infiltration of the Balkans had begun. The `tourist traffic' to Bulgaria ended on 1st March, when German troop formations openly entered the country and, screened by Bulgarian divisions posted along the Greek frontier, started to advance south. In Yugoslavia, there had been a hitch. On 25th March the right-wing Yugoslav Government joined the Axis, but two days later they were overthrown by a sudden coup d’état and a new pro-Ally Government began to make hasty preparations to resist invasion and to co-ordinate military operations with the Greeks. They had too little time. On 6th April, Germany declared war on Greece and Yugoslavia. Strong German forces, operating from Southern Bulgaria, attacked the fortified Greek positions in Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace, and another thrust was made against the southern Yugoslav front towards the Strumnitza Valley, with the object of driving a wedge between the Yugoslav and Greek armies. The attack on the Greek fortifications, despite the overwhelming strength in men and equipment of the Germans and their complete air superiority (the Greeks had no air support in this sector), was smashed with heavy losses. But the Yugoslav front soon broke and the Germans pressed on to Salonica. The northern Greek capital fell on 9th April and troops in north-east Greece were isolated. After having repulsed all enemy attacks with incredible bravery, they were now forced to capitulate.

»top

A month before, when the Germans' intentions had become obvious, the Greek Government had asked the British to land troops in mainland Greece. Until then, in order not to 'provoke' Hitler, British help had been confined to one brigade which occupied Crete and five R.A.F. squadrons, which in March had had to be substantially reduced to meet urgent demands in the Middle East. Now two British infantry divisions and one armoured brigade had arrived, and were in position south of Salonica.

By 13th April, the allied forces had withdrawn to a line from just north of Mount Olympus to Kozani. In the next few days they again withdrew to a line from Kalabaka to Thermopylae, where they fought their last big defensive action. In the meantime, another German drive had cut behind the Greek army in Albania. On 23rd April, after the fall of Janina and Florina, its commander signed a formal armistice. He later became Greece's first Quisling Premier. But the Greek Government in Athens, seeing that the situation was now hopeless, had already invited British troops to withdraw. The evacuation began on 24th April, and the Government moved to Crete. Three days later the swastika was hoisted on the Acropolis in Athens.

The last phase began on 20th May when the Germans attacked Crete. On 1st June, allied troops withdrew. The Greek campaign was over.

* * * * *

That, very, briefly, is the story the official communiqués told between October, 1940, and June, 1941. But there are many stories which they could not tell: stories of Greek soldiers, ill clad, ill fed, and ill equipped, dying of frost-bite (there were 10,000 amputations for frost-bite in the Athens hospitals) and exhaustion on snow-bound mountain-tops; stories of peasant women toiling up those mountains with supplies and ammunition for their men; stories of generosity and friendliness in every town and village through which our retreating forces passed—though the people knew only too well what was waiting for them when their British allies left. And there were other stories: dark rumours of betrayal and collaboration in high places, of pro-German ministers and generals appointed by Metaxas who, after the Nazi attack began, paved the way for invasion by military sabotage and political intrigue.

The Dictator himself had died in January, 1941, at the height of Greek military success, and what went on behind the scenes is still the secret of 'well-informed circles' in Athens. Until the archives are published and the full facts known, it is not for the foreigner to make `revelations.' But no secret can be kept in Greece for long. The people already know a good deal of what occurred that spring—and suspect more. Their bitterness against the dictatorship was the greater, when the occupation began, because they felt that but for the treachery of some of its nominees, the campaign might have lasted longer, the Germans might even have been held somewhere on the Greek peninsula.

CHAPTER V»top

The Occupation

Until the end of 1942, Hitler's chief motive in occupying Greece was the maintenance of lines of communication to North Africa and eventually (he hoped) to Syria and Iran. After that Greece became his outermost defence-line against the Allies in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Soon after German troops had completed the occupation of the Greek mainland and islands, the military administration of the country was divided between them, the Italians and the Bulgarians. The German command, however, remained the final authority in Greece, and hoped, by the partition, to secure effective control while keeping the smallest possible number of its own soldiers in the country.

The Bulgarian army, which had taken no part in the fighting, moved into Greek Thrace and Eastern Macedonia in the rear of the Germans. The `reunion of the liberated Aegean provinces' with Bulgaria was at once proclaimed by Sofia, and a purely Bulgarian administration was set up. This was the bribe for joining the Axis that spring. For the Greeks who lived in these areas (the 1922 exchange of populations had left them wholly Greek) it meant the choice between giving up their nationality, their language, their religion, and even their Greek names, or being exterminated or expelled. Many thousands abandoned everything and fled south to Athens and Central Greece. To take their places families of Bulgarian `colonists' were settled, and two years later the Bulgarian Government was boasting that over a hundred thousand had already been installed. In July 1943 the Bulgarian zone was extended west to within a few miles of Salonica.

»top

The Germans themselves retained direct control of Salonica and a large part of Western Macedonia, of certain areas and islands near Athens, and of Piraeus, the capital's great port. They also held three of the islands near the Turkish coast, most of Crete, and a narrow strip of land along the Greek-Turkish border in the extreme north-east.

For two years and three months, the rest of Greece was under Italian control. The Ionian Islands off the west coast were annexed to the `King-Emperor's' domains and plans were made to hand a part of north-west Greece to his Albanian subjects. But in September 1943 Mussolini's Empire collapsed. In Greece (with the help of the guerillas) the Fascist armies `evaporated,' and the Germans once again took over.

* * * * *

Some details of the sufferings of the Greeks during the occupation—by famine, by massacre and by reprisal—were smuggled out of the country at the time. Since the liberation, the official statistics of the deaths from starvation and execution, of the burning of villages, and the destruction and looting ill the towns and countryside, have been compiled in Athens. But statistics are dry reading, however horrible their message. One of the tragedies of the war has been the hardening of the heart of humanity: we have become so sated with atrocity and frightfulness that mere descriptions of human misery and degradation, however vivid, have lost their meaning. Those of us who have not lived through a Nazi-Fascist occupation will probably never understand just what the victim peoples have had to undergo. And yet it is only after understanding what three or four years of organised brutalisation can do to a nation and its citizens, that one can really follow the post-liberation problems of our European allies.

There are several reasons why Greece paid a higher price than any other occupied country (except perhaps Poland) for her defiance of the Axis. First, it was unexpected, and it threw badly out of gear the military plans of the dictators. Second, it damaged the prestige of one of the Axis armies beyond repair: Mussolini never outlived the ridicule resulting from his Greek defeat. Third, the Greeks, once they are roused, are an impossible people to subdue: the invaders, as their frustration and exasperation grew, fell back on ever cruder and more brutal methods of suppression.

And apart from all this, Greece in 1941 had still not fully recovered from her last series of wars. She had fought continuously from 1912 (when the first Balkan war began) until 1922. In 1922, with a population of five millions, she was suddenly forced to absorb one and a half million refugees. And even after nineteen years of uneasy peace, Greece was not a prosperous country. Despite great advances, the bulk of her peasant population lived dangerously near subsistence level: and they relied (unlike their Balkan neighbours) on imports for a big proportion of their food—including half a million tons of wheat each year. That was why, in January 1942, after the great Athens famine, Britain broke the blockade of Axis Europe and made one exception: Greece. But to-day, four years later, and more than a year since the invaders left, the Greeks are still almost starving: and as I write these words Greek children are dying, their health so broken by war-time hunger and distress that they cannot live through another winter.

CHAPTER VI»top

Cairo and Whitehall

The death of Metaxas, in January 1941, had faced King George II with a problem. Should he now repudiate Greek fascism, form a coalition government of all parties, and thereby end (or try to end) political disunity in Greece? He failed to do so. His first new Premier, banker Korizis, shot himself when the German invasion began (because of treachery, it was said, by the fascist ministers in his Government). For a short time King George was his own Prime Minister. Then, just before the collapse, a former liberal politician took over. Premier Tsouderos had himself been imprisoned by Metaxas, but Security Minister Maniadakis and other fascist nominees stayed in the cabinet, which followed the King into exile. Later they were sacked—but the King's last chance to form a democratic government while still on Greek soil was missed. So the `Royal Hellenic Government' in Cairo (they and King George reached Egypt on 28th May) were out of touch with new political currents inside Greece, and isolated from the resistance movement. For a year the King and his Ministers even declined to move a formal declaration repudiating the Dictatorship, with the result that they were popularly regarded as its successors and their eventual return to Greece a threat to Greek Democracy. In this way, from the beginning of the occupation, there was no contact, no commity of action, between the Greeks in Greece and their legal representatives abroad. This difficulty was never really overcome until immediately before the liberation.

* * * * *

Very soon after the occupation, and in sympathy with the general revulsion of public opinion, the leaders of all the pro-Metaxist parties, royalist, republican and left-wing alike, declared their opposition to the return of the King until the Greek people had decided by a plebiscite whether they wanted to live under a monarchy or a republic after the war. In February 1942 a secret but formal agreement to this effect was signed by the politicians in Athens. The text was smuggled out to Cairo—but the King remained adamant. Had he accepted the principle of the plebiscite then (as he eventually did), later history might have been different. But he still refused to compromise.

* * * * *

Meanwhile in Whitehall (the British Prime Minister took a very personal interest in Greek affairs), Greek politics were seen as quite a simple problem. King George had led his country into the war against the Axis. He was a 'very gallant ally' and, as such, merited all the support the British Government could give him. It was their `hope' that he would be `welcomed back by his people' when Greece was freed, and nothing was to be done by any British official or department to `prejudice his chances of return.' In justice to Mr. Churchill and the Foreign Office, it must be admitted that, at the beginning of the occupation, their information about Greece was so inadequate (and had been for some years) that they were apparently genuinely unaware of the strength of republican feeling, of the violence of the reaction against Greek fascism, or, indeed, of the fact that General Metaxas' regime had been a fascist dictatorship at all. It was surprising how little a pre-war British legation in the Balkans could know about the state of public opinion. There were those who said that it was no less surprising, once the occupation had begun, how well the British Embassy to Greece in Cairo could make its political despatches tally with what it knew the authorities in London would like to hear.

It was not long before the first party of Greeks escaped across the Eastern Mediterranean and political reports began to reach the Middle East. But Greeks who came to London said that these reports, and the clear political picture they gave, somehow never reached Whitehall in quite their original form. Because British policy in 1942 and 1943 was based on partial information, and because no one but the officials knew what was really going on, mistakes were made which might have been avoided and which, many Greeks believe, were the prelude to the civil war of December 1944.

CHAPTER VII»top

Resistance

All over Europe, the pattern of resistance was very much the same. I remember being surprised, when I came home to London early in 1944, by the description of events in his country given me by a member of the Belgian underground. Practically everything he told me—of right-wing collaboration, anti-royalist reaction, and left-wing resistance leadership—would have applied, with a few minor changes in names and dates, to what was happening in Greece. And it was natural that the resistance pattern should be much the same all over Europe. The occupied peoples were facing the same invaders using the same methods of oppression, many of their pre-war problems (whether they had had fascist 'appeasement,' or democratic governments) had been similar, and their post-war aspirations were very much alike.

Greece was no exception. The reaction against Dictatorship, allied pronouncements about Democracy and freedom from want, the desperate conditions to which the working and middle classes were reduced by the occupation—all these factors combined to strengthen the left wing. Therefore it was the left which took the initiative in starting the first organised resistance movement.

* * * * *

The central committee of the E.A.M. was formed in Athens a few months after the occupation. One of its great assets was that it was able to build on what was left of the Communist Party's underground network. But its original membership included a majority of non-Communist (though left-wing) leaders, and from the first it made efforts to recruit support from the `old' politicians. In that, it failed: partly because of their suspicion that they would be joining a Communist-dominated organisation though, at that time, they could easily have 'swamped' attempts at Communist control); partly because five years of political isolation had made them cautious (some of them were even doubtful of the wisdom of having a resistance movement at all) ; and partly because they got no encouragement from London or G.H.Q. Middle East, to join.

E.A.M.'s first major task was to organise its propaganda services. This was done rapidly and efficiently, and by the autumn of 1941 a whole series of regular printed `illegal' publications were circulating in Athens and Salonica, and E.A.M. slogans had become a constant feature on their walls. Membership began to grow, and with it outbreaks of `passive resistance': sabotage in Axis-controlled factories, strikes, and demonstrations. From the end of 1941 onwards, there were continual civil disturbances in Athens, and minor outbreaks elsewhere. In October a three-day strike in the capital marked the anniversary of Mussolini's Albanian attack. There were student demonstrations in November. On 25th March, 1942, three thousand Athenian students and citizens commemorated Greek Independence Day. In April the civil servants struck, and, when the students joined them, the University was closed. Early in July there was a mass demonstration in Athens in which eight thousand people took part, supported by simultaneous demonstrations in provincial towns. The climax was reached in the spring of 1943. The Quisling Government planned a decree (it was actually published in Salonica) making all Greeks between 16 and 45 liable for forced labour for the Axis: if necessary away from home. In January the trouble started. By February, crowds twenty- five thousand strong were marching on the puppet Premier's office and burning the archives of the Ministry of Labour. Early in March another major demonstration was only broken up by enemy armoured cars, machine-guns and hand-grenades. Twenty civilians were killed, a hundred wounded and thousands put into gaol.

But the `passive resistance' went on. By 10th March the invaders and their puppet government were beaten. They announced the immediate release of all arrested persons, a 48 per cent increase in wages and (the final surrender) the cancellation of the civilian mobilisation decree. Soon afterwards the Quisling Premier (the second) was sacked. The people of Athens had won. Their struggle continued, despite the Axis terror, daily more brutal, right up until the liberation in October 1944. But in the meantime the focal point of Greek resistance had shifted to the mountains.

CHAPTER VIII»top

The Guerillas

The `Greek People's Liberation Army' (E.L.A.S.) was started by E.A.M. in 1941. By the late summer of that year they had their first guerilla band operating on Mount Olympus. But the first big guerilla action was not fought till November 1942, after the arrival of a group of British liaison officers in Central Greece. With their help, 150 guerillas (100 of them were an E.A.M. contingent) attacked and destroyed the Gorgopotamos bridge, cutting rail communications between Athens and Salonica and interrupting the flow of German supplies to North Africa at a vital moment in Rommel's campaign. The Germans then took over the protection of the Athens-Salonica line.

From then on, the E.A.M. guerilla army gradually expanded all over Greece. By the summer of 1943 it had `freed' about a third of the mainland; with the Italian capitulation in September it acquired great quantities of Italian arms and ammunition; and by the end of the year the total membership of E.A.M. (military and civilian) was variously estimated by British liaison officers on the spot at between two hundred thousand and `a quarter of the whole Greek population.' When liberation came, E.A.M. controlled almost all Greece except big towns, strategic points and lines of communication held by the Germans, and a small area in the north-west where, with British support, the last `nationalist' guerilla band had managed to survive.

Organised on military lines, the E.A.M. troops took orders from a G.H.Q. in Central Greece. At the head of each unit were three men: a capetanios or guerilla leader, a military commander (often an ex-Greek army officer), and a political adviser. Actual control was usually in the latter's hands—and he was usually a Communist. This, and the fact that, towards the end, Communists occupied most of the positions in all branches of the E.A.M., was at least partly due to their superior training and experience in organisation and subversive work. Militarily, the system functioned well. Discipline was better, and less dependent on personalities, than in the other guerilla bands.

* * * * *

It is true the Greek guerillas did not have to their credit successes as spectacular as those of their comrades in Yugoslavia. Certainly the chief reason was because much of their effort was wasted on the feud between E.A.M. and 'nationalist' groups: a feud which culminated in civil war after the liberation. Probably that feud could have been settled long before, if our liaison officers inside Greece had had clear instructions whom to support, and if Greek democrats had felt able to trust our political intentions. But as long as we made the Greeks believe that we were resolved to `sell' King George, and to build up `nationalist' opposition to E.A.M., our appeals to them to forget politics met with a sceptical response.

Nevertheless, Greek resistance was a very definite military asset to the allies. It immobilised between fifteen and twenty enemy divisions during the occupation, proved a constant and serious embarrassment to them, and on several occasions deceived the German High Command about allied intentions —for example, in the summer of 1943 when, after a series of guerilla operations against communications in the north, three extra German divisions were sent to meet an expected invasion of Greece.

Later events for a time overshadowed the good work of the guerillas and the underground, and concentrated attention on their mistakes and crimes. To-day their struggle must be seen in true perspective, if its political legacy is to be understood.

CHAPTER IX»top

The `Nationalists'

The first of the `nationalist' guerilla leaders, Colonel Zervas, took to the mountains in September 1942. From the outset, his organisation was British-sponsored, and it was a British agent who persuaded him, after he had refused the post of Commander-in-Chief of the E.A.M. army, to leave Athens and form a band near his home-district in north-western Greece. That November, fifty of his men, with himself in command, took part in the joint attack on the Athens-Salonica railway already described.

Politically unstable, Zervas had been involved in successful and unsuccessful coups d’état ever since the end of World War No. I. Now he left Athens a declared republican. In March 1943, noting the way the British wind was blowing, he sent a telegram of loyalty to King George. Later, when it became clear that his organisation was the only one which offered serious opposition to E.A.M., more and more right-wing and royalist officers joined him. He had become the Greek Mihailovic. So close was the parallel indeed, that in the summer of 1944 the Cetnik leader, after his repudiation by the British, was said to have suggested collaboration with Zervas against E.A.M. and Tito's Partisans. The full story is not known—except by Zervas; and he, abandoned by most of his early resistance followers, is perhaps unlikely to tell.

* * * * *

»top

His first trouble with E.A.M. was in the summer of 1943.

But in July, a pact was signed on the initiative of the chief British liaison officer in Greece whereby E.A.M., Zervas' forces, and two other small `nationalist' bands, were allotted areas in which to operate, and agreed to work together and respect each other's integrity. For a while they did so—but such a compromise was bound to crack. Zervas and E.A.M. could no more co-operate than Mihailovic and Tito. In October new clashes took place and lasted until February, when British intervention again saved Zervas from elimination and a new agreement was patched up. Some fifteen hundred guerillas left him then, and thereafter his forces never exceeded five thousand, and remained confined in a small enclave on the north-west coast. They survived until after the liberation, and in the civil war Zervas offered General Scobie his help in destroying E.A.M. Ten days later he found himself on the island of Corfu. His army had disappeared.

* * * * *

Zervas was not the only anti-E.A.M. leader who `cashed in' on the British. He was merely the most successful. In the Peloponnese and round Salonica other right-wing army officers started small bands in 1942 and looked to Egypt for support. E.A.M. developed later in the South than elsewhere and, when in 1943 its organisers began their work, they were in no mood for compromise with the `National Resistance Organisation' of the Peloponnese. They broke it up. Some of its leaders joined E.A.M., others, though originally helped and equipped by our liaison officers, turned quisling and joined the German-sponsored `Security Battalions.' Round Salonica, developments were much the same. By September 1943, the `Panhellenic Resistance Organisation' (semi-quisling from the first) had also ceased to exist as a guerilla force.

In eliminating 'nationalist' groups, E.A.M. methods were often tough. One action in particular shocked public opinion, and did E.A.M. prestige no good. Colonel Psaros was a respected Liberal and an efficient officer. His first guerilla unit was formed early in 1943, and his forces at one time reached a strength of two thousand men. They were twice disbanded by E.A.M. in 1943, and twice, thanks to British intervention, permitted to reform. After a third attack in April 1944, Psaros himself was murdered and his force finally destroyed. A number of his officers then joined the `Security Battalions.'

Such was the fate of the "nationalist" bands.

CHAPTER X»top

British Policy

At this point, the reader may well object that however imperfect the information they received, Whitehall and Downing Street must by now have got to know that things were going wrong in Greece, and that the seeds of civil war were being sown. And indeed it was in August 1943 that the first delegation of guerilla leaders—spokesmen for E.A.M., Zervas and Psaros—arrived in Cairo. They came for political and military discussions with the British, which, they hoped, might lead to unity of action inside Greece, and the formation at last of a coalition Government in Middle East in which Greek Resistance would be represented. Their mission failed. The reason for its failure? The King again refused to accept a plebiscite to decide for or against his restoration, and threatened to abdicate if he were pressed. London took fright, and Cairo packed the delegates off home.

* * * * *

Whatever the intentions may have been, British Policy in 1942 and 1943 was difficult to understand. The Foreign Office was working for the King's return. The King refused to make the one concession that might (at least in the early days) have paved the way. At the same time, the military were busy "stimulating resistance" and calling on the Greeks to forget politics until after the war. As a result, there was little co-ordinated action by the various British authorities in Middle East. The few press reports that leaked out of Cairo at the time told of an inter-departmental tug-of-war that went on for months: diplomats on one side, soldiers on the other. Eventually, they said, it was the diplomats who won. After the autumn of 1943, the whole responsibility was theirs.

One of the tragedies of the situation was that the British Government policy was helping to bring about just that situation which it sought so desperately to avoid. Instead of making Greek resistance more moderate, more democratic, more truly representative of the mass of Greek opinion, we drove it to extremes. Instead of helping to strengthen E.A.M. by encouraging non-communist elements to join, we tried to weaken its influence, to prevent it `monopolising' the liberation movement, by aiding its political opponents. The `nationalists' we tried to use were just those people with whom German propaganda against the `red menace' was most effective. And Göbbels was working day and night to prove that all resistance to the Germans was communist inspired. Little wonder that so many of our `nationalist' friends turned frankly quisling.

* * * * *

Meanwhile the E.A.M., baffled and frustrated, became more and more Communist and more extreme, and reports that it was `terrorising' the peasants in the areas it controlled became more frequent and more credible. By the end of 1943, however, it was infinitely the strongest military force in the country (apart, of course, from the occupation troops), and in the spring of 1944 it set up a Political Committee, held `elections,' and became in fact the Government of Free Greece.

CHAPTER XI»top

`National Unity' and Liberation

At this stage the Greek forces in the Middle East took a hand in the affairs of their country. The Army, after fighting well at Alamein, had mutinied once already (in March 1942) in protest at the appointment of royalist officers to command it, and had forced the resignation of its Minister of Defence. A purge of `extremist' soldiers followed. The Navy had been on operations continually since the beginning of the Albanian campaign. After the 1941 evacuation—in which it played a notable part—it had been expanded by the addition of a number of British vessels. It had done useful and hazardous work in the Mediterranean, and three Greek naval units took part in the Normandy landings.

Now both services mutinied—in protest at the failure of the Greek Government in exile to establish contact with the resistance movement and the new Political Committee inside Greece. The mutiny was crushed with the use of British troops—but the Greek Government fell. The new Premier called a conference with political and resistance leaders from Greece which met on Mount Lebanon in May 1944.

»top

Despite a tense atmosphere with charges of terrorism and counter-charges of collaboration flying between representatives of `nationalist' groups and E.A.M., a formal agreement of unity—the `Lebanon Charter'—was signed before the conference broke up. But when the new Government was formed, E.A.M. was still not represented in it. It was not until 2nd September, despite their reluctance to serve under bitterly anti-communist Premier Papandreou, and after extreme British pressure, that six E.A.M. Ministers agreed to join. Nominal national unity had at long last been achieved … but it had come too late. On 6th September, the Government moved from Cairo to Caserta. The German withdrawal from Greece had begun.

* * * * *

The news of the withdrawal `broke' on 11th September, when Turkish reports described the German evacuation of some of the Aegean islands. It came as no surprise. Allied commanders had expected such a move for months (the progress of the war on other fronts forced Hitler's hand), and their plans were ready.

Guerilla operations had intensified during the summer (and, with them, `passive resistance' in the towns), and the German occupation forces' morale was very low. They naturally did not relish the prospect of a retreat right through the guerilla-ridden Balkans, and at the end of August there had been serious mutinies in the Peloponnese. The result was that when British troops arrived there was little heavy fighting to be done. There were a few sharp encounters in the north of Greece, but the result of the campaign was a foregone conclusion, and the force sent in under General Scobie's command was small.

CHAPTER XII»top

The Final Crisis

To the outside world it looked as though, politically as well as militarily, the liberation of Greece was going well. In mid-September, the first Greek Government delegates arrived in the liberated areas. In the Peloponnese, Canellopoulos, a former vice-Premier, did an extensive tour with the local E.A.M. commander, and reported that he had met with an enthusiastic reception and had found the situation well under control. On 18th October, the Government itself reached Athens amid general celebration. After a minor reshuffle of cabinet appointments, Premier Papandreou announced that the re-establishment of normal peace-time conditions would now begin.

In May, the question of the restoration of the monarchy had at last been shelved: that month King George had formally undertaken not to return to Greece until after a plebiscite had been held. His part in the liberation was confined to a broadcast message from London. It must have been a galling moment for him when the British Government at last realised that in the existing state of Greek opinion they could no longer recommend his immediate return.

But the constitutional issue was now the least of Greek political problems. Under the cover of temporary `national unity,' the bitter antagonisms of the occupation still smouldered. By force of circumstances—their own recent political history, the tactics of the invaders, the blunders of the Greek Government in exile and (alas, not least) of British policy during the occupation—the Greek people had been divided into two irreconcilable extremes.

On the left was the E.A.M.—now communist-dominated; exasperated by repeated, clumsy, and obvious attempts from the Middle East, ever since 1942, to weaken it; intensely suspicious of British intentions and of the anti-E.A.M. Premier and Ministers in the Greek Government; but conscious that, now the Germans had left, they were by far the strongest military power in Greece.

On the right were the `nationalists': British protégés (like Zervas); victims of E.A.M. reprisals; people who feared the Left and `revolution'; and those who had fallen for German propaganda and turned quisling or joined `Security Battalions.'

But whereas E.A.M. was a positive force with a compact mass following, the `anti-E.A.M.' (as the difficulty of finding it any other name itself implies!) was a motley collection of individuals and groups who, with varying motives and different reasons for their attitude) were only held together by their hatred of E.A.M.

* * * * *

Greece had had political antagonisms in the past. Ever since her liberation from the Turks a century before, Greek history had been punctuated by revolutions and coups d’état. Those revolutions had been child's play compared with what was coming now. Never in any modern political upheaval had there been protracted fighting or really serious loss of life. Mass 'atrocities' in Greek politics were unknown. Why had things changed?

They had changed for two reasons. First, never before had the cleavage between the two opposing sides gone so deep. Extreme though the old pre-war royalist-republican feud sometimes may have seemed, there was always a moderating influence on one side or the other, almost always there was a basis (at least in theory) for some kind of compromise. There were no moderates, and there could be no compromise, in the December civil war.

Second, the years of dictatorship and occupation had left their mark. Sooner or later every cause has its effect. You cannot preach fascism to a people (even a people as individualistic and intelligent as the Greeks) for four years without doing sonic damage to the minds of some sections of that people. You cannot subject a nation to organised Nazi brutalisation (even a nation which resisted it as stoutly as the Greeks) for three and a half years without having some effect, conscious or unconscious, on the moral standards and reactions of that nation.

Fascism and Nazi occupation are a disease. Liberation is not the end of the cure—it is the beginning. It will be years, in Greece and in all the liberated countries, before the process of rehabilitation—material, political, and moral—is finally complete.

* * * * *

The liberation 'honeymoon' lasted for just two months; but under the surface things started to go wrong almost at once. First there were rumours of E.A.M. massacres and a `red terror' in the south of Greece. At the same time, the Left began to complain that Premier Papandreou was protecting `nationalist' quislings. Royalist and right-wing officers, they said, some of whom had even served in the German-sponsored `Security Battalions' were not being arrested—many were being given new commands. The same applied to quisling government officials. The promised purge of collaborators was not being carried out.

On 11th November the first clash between royalists and E.A.M. was reported from Athens. It was a small affair, and was followed by a few arrests.

Meanwhile in the Government of `national unity,' fierce ministerial discussions were going on. The issue was the demobilisation of the resistance forces. The Premier and his friends insisted on the disbandment of all `private armies' as the first step to re-establishing the rule of law. Since before the invasion, Zervas and the E.A.M. cornrnander-in-chief had formally placed themselves under the orders of General Scobie, and the latter now reinforced the Prime Minister's demands. But E.A.M. claimed that since the mutiny in April, when the Free Greek Forces in Middle East had been reorganised and `subversive elements' interned, those forces (one brigade of which had recently distinguished itself in the fighting for Rimini), now officered and commanded exclusively by the right wing, were as much a `private army' as their own. There was an element of truth in what they said.

The E.A.M. Ministers therefore proposed that, together with their army and Zervas' bands, the Free Greek Forces from abroad should also be disbanded, and the City Police and Gendarmerie (which had continued to function during the occupation) should be reorganised and purged. At this point the two groups reached deadlock. On 2nd December the six E.A.M. Ministers resigned.

* * * * *

On 3rd December a large E.A.M. demonstration, banned at the last moment by the Government, marched towards Athens' Constitution Square. Exactly what happened that morning is still the subject of violent controversy, but there is no doubt that the police opened fire and that a number of the demonstrators (who were all apparently unarmed) were killed.

The formation of a new coalition government was now attempted. Premier Papandreou had offered to resign and the veteran Liberal leader Sophoulis had been successful, he claimed, in forming an alternative all-party administration and was ready to take over. But King George in London refused to accept Papandreou's resignation, and Sophoulis (according to his own account) was warned by the British Embassy and General Scobie that it was not the British Prime Minister's desire to see a change of government in Greece just then.

On 5th December the civil war began.

CHAPTER XIII»top

The Civil War

The fighting in Athens in December 1944 and January 1945 was variously described, at the time and afterwards, as a `communist revolt,' `the second liberation,' `British reactionary intervention,' and `the maintenance of law and order.' There are arguments to support each one of these descriptions.

It is true that, by December, E.A.M. was dominated by Communists who were trying to seize power, and under whom, had they succeeded, there would have been little hope of democracy (as we understand it) in Greece. It is also true that in many of the E.A.M.-controlled areas the inhabitants were living under a terror regime which, many of them told me, had become worse than German or Italian occupation. For them, the end of the civil war was in fact a `second liberation.'

On the other hand, without British intervention, the fighting would have finished in a few days, perhaps a few hours. E.A.M. would have taken Athens over, set up a `people's' government, and then doubtless proceeded to eliminate its active political opponents—on the grounds that they were Fascists or collaborators. And so indeed many of the more violent of them were. In the street battles which were fought in the capital, the British tanks and armoured cars had no more enthusiastic helpers than the extreme `nationalist' groups. Conspicuous among them, incidentally, was `X,' which in January 1946 staged the Kalamata `revolt' in southern Greece.

At British Headquarters, however, the problem was military, not political—and, with the small forces at General Scobie's disposal, it was an extremely difficult military problem at that. In the official view, the task of the British troops was to `protect the legal and constitutional Government of Greece against attempts to overthrow it by armed violence.' Their case was the stronger in that, since before the liberation, the E.A.M. was theoretically under General Scobie's command, and had disobeyed his orders to disband.

* * * * *

We are still too close in history to the Greek civil war to be able to weigh up with complete accuracy all the pros and cons. Certainly at this stage, a year after the event, the easiest course for any commentator would be to decide for or against the E.A.M., and then uncompromisingly to justify or to condemn. But unfortunately political problems are never as simple as that: one cannot divide the factors into black and white. And, above all, the objective observer has to remember that every political action, however `wicked' it may seem, is the result of something that has gone before.

On this basis, one can arrive at the following conclusions:

(1) The Greek civil war might never have happened if the policy in Cairo and London during the occupation had aimed at unifying the resistance movement rather than building up a `nationalist' opposition to the E.A.M. That policy was largely based on a fear of the extreme left wing. But its result was to make the left (which in Greece, as elsewhere, was bound to be the core of resistance) more extreme, to eliminate the moderates, and to push the `nationalists' into the arms of the Germans.

(2) Once the E.A.M. attempted to seize power, the British had to intervene. However biased our past policy, however understandable the extremism (by then) of E.A.M., its victory would have been the end of democracy in Greece. We should have been responsible. We had no alternative but to fight.

(3) The civil war really started long before the liberation. If it was our intention to crush `all attempts to seize power by violence,' we should have sent a larger force to Greece. But our officials went on insisting that E.A.M. was a `small minority of gangsters,' and would evaporate as soon as British troops arrived, So the fighting which, had General Scobie's force been bigger, might never have started, lasted for five weeks.

(4) The only ultimate justification for our intervention, the only complete atonement we can make for past mistakes, is the final establishment of a free, stable, and effective democracy in Greece.

* * * * *

The E.A.M.'s first move was to declare a general strike on 4th December. Next day there were attacks on Government troops and on police stations and prisons throughout the Athens area. British tanks came to their defence. On the 6th the centre of the capital was cleared of `rebels' and the E.A.M. offices captured. By this time General Scobie's forces were heavily involved. On 10th December, E.A.M. launched an attack on the Zervas enclave in northwestern Greece, and the last `nationalist force in the provinces was soon in full retreat.

Elsewhere, outside the Athens area, E.A.M. was in complete control. There was a clash with Indian forces in Corinth on the 15th, and on the 17th, after trouble round Volos, the Indians were evacuated from western Greece. But in Salonica and the North there was no fighting throughout the five weeks of `civil war.' For most of the period the few British troops in that area remained on friendly terms with the local E.A.M. administration—largely thanks to the tact and authority of their commander, General Bakirzis, a former Greek army colonel who had won a British D.S.O. in World War I. It was a curious situation.

But in the capital, bitter battles were going on. E.A.M. began to shell the centre of the city, and British aircraft were called up to silence the `rebel' guns.

* * * * *

By now, world opinion was getting restive, and the British Government was being called upon to justify its actions. Field-Marshal Alexander and our Resident Minister in the Mediterranean arrived in Athens on 11th December. They failed to arrange a truce, and on Christmas Day the British Prime Minister and his Foreign Secretary flew to Greece. A conference was summoned in the old Palace at Athens, and there, with the noise of gunfire echoing in the streets around them, the British Ministers met representatives of E.A.M., of the Government, and of the `old' political parties.

The fighting was still going on when Churchill and Eden left Athens three days later. But the conference had achieved two results: a regent was appointed and Premier Papandreou fell.

During the dictatorship, Damaskinos, elected Archbishop of Greece and Metropolitan of Athens, was exiled by Metaxas and replaced by a Government nominee. He was reinstated when the occupation began, and his work in saving hostages from the Germans and organising famine relief in Athens had won him the respect of all patriotic Greeks. He now assumed the functions of Head of the Greek State until the question of the King's return should be finally settled by a plebiscite. The King officially confirmed his appointment on 31st December.

The new Prime Minister, General Plastiras, had also been in exile for many years. Leader of a republican revolt in 1922, he was a staunch Liberal, and, despite his fierce denunciations of E.A.M. during the Christmas conference, he was likely to be more acceptable to the Left than M. Papandreou.

By now it was becoming clear that the British would go on fighting until a settlement was reached (pressure of public opinion on the Government in England had exacted no concessions), and that E.A.M. could not expect outside military or diplomatic help. Indeed the absence of Soviet support puzzled many people. It is true that Russia then was heavily engaged elsewhere. But at no time during the occupation was there evidence that E.A.M. was being run from Moscow (though various interested parties would have liked to have proved otherwise) and pro-E.A.M. propaganda in Soviet broadcasts was spasmodic and comparatively mild.

The struggle was therefore hopeless. On 11th January a truce was signed, and the next day the `Varkiza Agreement' formally ended the civil war.

CHAPTER XIV»top

The Reaction

The E.A.M.'s surrender, however, was not unconditional. Terms were laid down to protect members of the organisation other than those who had offended against the criminal code or the laws of war; and agreement was reached on the holding of a general election and a plebiscite to settle the constitutional issue. The Varkiza Agreement has lost most of its significance to-day. Some of its political provisions have been changed—with the agreement of E.A.M. The protection it should have afforded to former E.A.M. members was, during most of last year, ignored. It was, on the whole, natural that that should have happened.

During the civil war E.A.M. used against their opponents the kind of methods to which guerilla armies all over Europe had become accustomed in their struggles with the Germans. When they started to withdraw from Athens they took with them thousands of Greek hostages. Sections of the British Press head-lined these `atrocities' in support of the `British case.' Exaggerations there may have been but unfortunately these stories were largely true. As the fight went against them, the E.A.M. commanders lost their heads and became desperate. Before the end, all the important non-Communist leaders had publicly repudiated E.A.M.—except one: Tsirimokos, out of a sense of duty, stayed in the movement until the Varkiza Agreement had been signed. Then, when he had added his name to the list of signatories, he too resigned.

The first result of the civil war and the way E.A.M. had fought it was a strong popular reaction. A part of Greek opinion, always volatile, swung violently to the other extreme. For the first time since the Albanian campaign there was a mass royalist movement in Greece. The King's past failings were forgotten and, in many people's minds, he became the last bastion against red revolution.

The second result was that the `nationalists' felt that the victory had been theirs. Their turn had come to `get their own back' on the Left. And they believed that British intervention against one extreme meant British support for the other. So a `witch-hunt' for Communists began. Anyone who had been connected with E.A.M., in whatever capacity and at whatever date, became immediately suspect. Even `resistance' was now a term of scorn. It was the resistance movement, the `nationalists' claimed, which had betrayed Greece and reduced her to her present plight.

The Government, still predominantly right-wing under the new Premier, did not have an easy time. Probably no government at that moment could have been really impartial. So the gaols were filled with political prisoners, right-wing appointments were made through the Services and State administration, and collaborators and quislings went unpunished. It looked as though the `nationalists' had now come into their own.

CHAPTER XV»top

Changes in Whitehall

In July 1945, a new Government came to power in England. For a few days the E.A.M. rejoiced. Now, they thought, there would be a change of policy; Britain would withdraw her support from the Right and E.A.M. would take over again. They were soon disappointed. On 20th August, 1945, the new Foreign Secretary told the House of Commons: "His Majesty's Government adhere to the policy which they publicly supported where Greece was liberated. We stated then that our object was the establishment of a stable, democratic Government in Greece, drawing its strength from the free expression of the people's will." And he added that he did not want to see a change of Government in Greece.

But although there was no dramatic reversal of policy, a series of gradual changes did take place. The conviction, which still persisted, that because Britain had fought the extreme Left she now backed the extreme Right and wanted to assure King George's restoration, was eventually dispelled. Pressure was put on the Greek Government to `decongest' the prisons. But the major problem, in the new British Government's view, was economic rehabilitation. Until the Greek peasant and worker had a reasonable standard of living, political stability would never be achieved.

In October, Archbishop Damaskinos visited London for consultations with the Foreign Secretary. In November the British Foreign Under-Secretary went to Greece. Though his mission was in fact economic, not political, there was a change of Government in Athens before he left. The new Premier was Sophoulis, the Liberal leader who had offered to take over from Papandreou the day before the civil war began. His Government, a government of the `Left-Centre,' was committed to a programme of emptying the prisons, reorganising the administration, purging the services of quislings, and preparing for elections to be held in March, 1946. The plebiscite was to be postponed until 1948. By then it was hoped the bitterness of the civil war would have faded, and the devastation of the occupation be overcome. The Greeks would be able to take their decision in a calmer atmosphere.

The Sophoulis Government was still in power, and had made some progress in its programme, notably in the economic sphere (a British loan of £10 million to Greece was announced on 25th January, 1946) when the Soviet demand for the evacuation of British troops, because they were `endangering the peace of the world,' was received by the Security Council of the U.N.O.

CHAPTER XVI»top

U.N.O. Decides

The Council met on 2nd February to discuss the Russian charge. The Soviet Delegate explained that it was founded on "four main questions of substance:

"(1) There was prevailing in Greece a very tense situation, which might have very unhappy consequences not only for the Greek population, but also for peace and security.

"(2) The presence in Greece of British troops was not necessitated by circumstances, because there was no need to protect communications as in the case of troops in defeated countries.

"(3) The presence of British troops in Greece had become a means of pressure on the political situation in the country.

"(4) These circumstances had resulted very often in support for reactionary elements in the country against democratic ones."

And he added: "What happens to-day in Greece, the horrors perpetrated there, the White terror, is now widely known to everyone, and I think it is hardly necessary to bring proofs of that here."

The basis of the Russian case was that "the maintenance of order in any given country is a purely domestic matter; it is a matter which can be dealt with by the Greeks themselves and not by foreign troops," and further that "the presence of British troops has been used time and again by reactionary elements against democratic elements in the country ... and has brought added acuteness to the fight between these two factions." At one point he claimed for E.A.M. that it was "the united front of all the really democratic organisations in the country." And he ended his first speech to the Council by a demand for the "quick and unconditional withdrawal of British troops from Greece."

* * * * *

Mr. Bevin, putting the British Government's case, made a reply as vigorous and as blunt as the speech he had just heard. "I think the speech we have just listened to," he said, "… points not to the necessity of withdrawing British troops, but to the imperative necessity of putting more there." He went on to explain that this was not the first time that the British Government had been approached by the Soviet on the subject of Greece: "it has always been a counter-attack on Great Britain whenever we have raised a matter affecting some other part of Europe."

Before the liberation, it had been arranged that "British administrators and troops, with Marshal Stalin's agreement, should go into Greece and help revive the country, turn the Germans out, and seek to get order and civil government in operation. We went." The process of revival had been interrupted by "the Communists seeking to obtain a minority government to control the country." But when that was over, we did not appoint a British puppet regime. "We believe that democracy must come from the bottom and not from the top," and so we were allowing free "trial and error in Greece until she found strength in her democratic legs."

"I have been pressing the Greek Government," said Mr. Bevin, "to get on with establishing tranquillity in the country, to get the elections and let the British troops come home. . . . We do not want these forces there. But the Greek Government have stated over and over again `We must get settled Government, we must get the elections, and you, the British, must help us to do it'."

That was the basis of the British case, and the Foreign Secretary concluded by asking the Council for "a straight declaration; no question of compromise in this: Is the British Government, acting in response to the request of the Greek Government in lending some of its forces to help get order and economic reconstruction in that country, endangering the peace? I am entitled to an answer, Yes or No. If we are endangering the peace of the world, then you are entitled to tell us so and the British Government will take that answer into account immediately. If we are not, then we are entitled to a clean bill; We are entitled to be told we have done nothing at all to endanger the peace of the world."

* * * * *

Even before the Greek delegate had spoken, there could be no doubt what the verdict of the Council would be. M. Aghnides told briefly how British troops were in Greece at the invitation of the Greek Government, and how their continued presence was `indispensable' until normal conditions had been restored. He ended with "an appeal to the Council, and in particular to our great allies. … Help us to compose our differences. We will do it the sooner with your help."

* * * * *

Two days later, the Council met again to discuss Greece. No substantial new argument was brought forward by either side. In two further meetings the delegates of seven member states spoke: all rejected the Russian case. Thereafter the only problem was to find a way of expressing the Council's decision while, at the same time, closing the issue on a `note of co-operation.' Britain was cleared of any charge of endangering the peace by keeping troops in Greece, and the demand that they should be withdrawn was dropped.

CONCLUSION»top

The Final Verdict

Britain has been vindicated by the United Nations. But history will give the final verdict. The recovery of a country shattered by fascism, invasion, war, and civil war is inevitably a slow and painful process. It will take time for the bitterness and hatred to die down in Greece. It will take time for democratic institutions to grow strong and stable. To-day the British are in Greece to see that democracy is re-established. We have told the world that that is our only aim. Until we have discharged that obligation, Greek liberation will be incomplete.

THE END

DIARY OF EVENTS»top

| 1935 | .. .. | .. | King George II returns. |

| 1936 | August 4th | .. | Metaxas becomes Dictator. |

| 1940 | October 28th | .. | Mussolini invades Greece. |

| 1941 | January 30th | .. | Metaxas dies. |

| April 6th | .. | Hitler invades Greece. | |

| April 27th | .. | Athens falls. | |

| May 28th | .. | King George reaches Egypt. | |

| June 1st | .. | Crete falls. | |

| Autumn | .. | E.A.M. formed in Athens. | |

| Winter | .. | First E.A.M. guerilla band. | |

| Winter | .. | Great Athens famine. | |

| 1942 | January 27th | .. | Britain breaks blockade. |

| March 25th | .. | Demonstrations in Athens. | |

| September | .. | Zervas starts guerilla band. | |

| November | .. | Guerillas cut Athens-Salonica railway. | |

| November | .. | Free Greeks fight at Alamein. | |

| 1943 | March | .. | First mid-East mutiny. |

| July | .. | First E.A.M.-Zervas clashes ended by British mission. | |

| August 12th | .. | Guerilla delegates reach Cairo. | |

| September 8th | .. | Italy surrenders. | |

| October | .. | More guerilla clashes. | |

| October | .. | E.A.M. controls Peleponnese. | |

| February | .. | British mission negotiates E.A.M.-Zervas pact. | |

| 1944 | March | .. | E.A.M. forms political committee. |

| April | .. | Second mid-East mutiny. | |

| May | .. | Lebanon Conference. | |

| Summer | .. | Guerilla operations intensify. | |

| September 2nd | .. | Government of National Unity formed. | |

| September 11th | .. | German withdrawal begins. | |

| October 5th | .. | Allied landings announced. | |

| October 14th | .. | Athens liberated. | |

| October 18th | .. | Government reaches Athens. | |

| November 1st | .. | Salonica liberated. | |

| December 2nd | .. | E.A.M. Ministers resign. | |

| December 5th | .. | Civil war starts. | |

| December 25th | .. | Churchill visits Athens, calls conference. | |

| December 31st | .. | Damaskinos becomes Regent. | |

| 1945 | January 11th | .. | Varkiza agreement signed. |

| July 25th | .. | Labour Government elected in England. | |

| October | .. | Archbishop Damaskinos visits London. | |

| November | .. | British Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs visits Athens. | |

| November | .. | Sophoulis becomes Premier. | |

| 1946 | February 2nd | .. | U.N.O. Council discusses Greece. |